Universities are supposed to be dead. These bastions of higher learning have been on Silicon Valley’s hit list for much of the past decade, and disruption phasers targeting the industry have certainly been set to kill in the years since the global financial crisis.

And yet after years of efforts, we have arrived in 2015 and almost nothing seems to have changed about the way we get our degrees or even just our continuing coursework.

MOOCs – Massive Open Online Courses – were supposed to be the vanguard of the new online education movement, surging to popularity in 2011 and 2012 following a rash of press about the end of higher education as we know it. Since those discussions though, MOOCs seem to have fared poorly. Just take a look at their popularity:

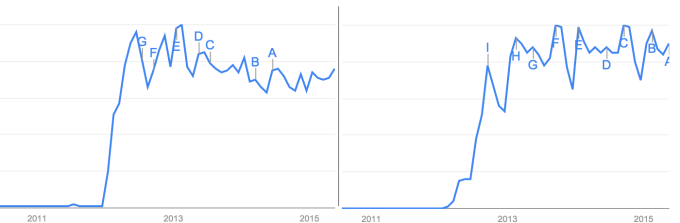

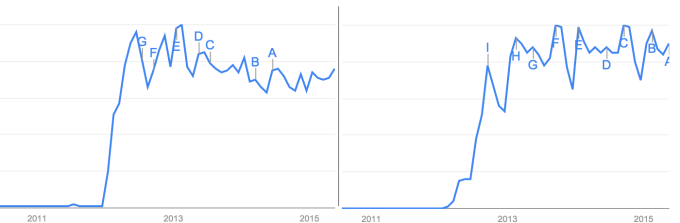

Coursera and Udacity’s Google Search Traffic

If we use Google Trends to search for the names of the two most well-known MOOCs, Coursera and Udacity, we see that both of them seem to have stalled in terms of search traffic, a sign of weak new user growth (one way VCs can get a feel for a startup’s word-of-mouth distribution is to look at its search traffic – if a friend mentions a new company, people tend to search for it on Google or the App Stores).

As any founder will try to convince you, traffic is not the only metric to judge a company, but it is one of the most crucial, particularly in a space like education where popular acceptance of a credential is critical to the success of the entire endeavor.

What happened to the revolution? Education is arguably the most important activity of our society, providing the basis of the knowledge economy and ultimately our prosperity in the modern world. There are incredibly smart people thinking about this everyday, both inside the ivory tower, and in colorful co-working spaces across the country. How could we go so wrong?

What the world is discovering is that humans are going to be humans (a discovery we seem to make a lot in startup-landia). We failed to ensure that motivation and primacy were built-in to these new products, and in the process, failed to get adults to engage with education in the way that universities traditionally can.

The Motivation Challenge

Just take one of the most repeated attacks against MOOCs: their incredibly low rates of course completion. Depending on the course, the signups to completion ratio can easily be in the low single percentage points, with an enormous drop in the opening weeks of a course as people either commit or leave.

New forms of online education like MOOCs lost both forms of primacy at once. By making them free, students had few incentives to not quit any time the course materials got boring or difficult.

This was, frankly, a dumb metric to condemn MOOCs over – it’s essentially the bounce rate for websites. Who cares?

However, motivation (and also patience) is the key ingredient for success in education. While drop off rates in course completion are partially indicative of the quality of the MOOC education product, they are far more valuable as a reflection of the limited dedication to continuous learning that most adults have in the first place.

I realize that this can be hard to accept in an industry like software startups where the rate of autodidacts is probably one of the highest in the world outside universities themselves. Nevertheless, there is a reason that teaching colleges spend so much time discussing how to inculcate lifelong learning, since that is simply not the default for most people. Family and job demands (aka life) can easily preclude this sort of on-going investment of time into education.

Besides lack of time though, the key challenge for open online education was connecting learning to more pecuniary outcomes, namely job performance, promotions, and new job searches. Outside of programming, which seems to be a unique area of learning with a high return on investment, few courses seem destined to transform a working adult’s job prospects.

Indeed, Google Trends as well as other media sources seem to corroborate the notion that MOOCs were more successful overseas, where students often have strong financial incentives to improve their skills but lack the kind of plentiful education that is available in the West.

Without internal or external motivation, online education products have faltered. All the structure of online courses ends up being just overhead compared to reading a book or an article, without any clear additional value either in terms of education or in terms of economics.

A Lack Of Primacy

The motivation problem should have been obvious from the start. Libraries and books have been widely available throughout the United States for easily the last century. While video lectures may be an improvement over books, there were also companies for years that sold lectures online or by mail order, albeit often at a steep price. Those who wanted to be educated had the means to do so.

There is another element to motivation though that is crucial to recognize in our early experiments with online open education, and that is the power of primacy. Primacy is making education the primary activity of a student’s day, or perhaps more specifically, the primary thought activity of the day.

Primacy is deeply connected to motivation, since it makes learning the default rather than a conscious decision that we make throughout the day. Furthermore, primacy also allows us to peer deeper into knowledge, since we can make connections between facts and theories that we might otherwise miss out on.

When we attend a physical university, we automatically give primacy to education. There is something about the configuration of a college campus, the schedule of courses, and the mobs of students roaming around that places us in a mindset for learning.

There is also financial primacy that comes from paying large tuition bills. Traditional forms of online education through universities like Kaplan or University of Phoenix still benefit from this sort of primacy, since students are paying incredible sums to receive their education. Money speaks to us, especially when it is leaving our bank account thousands of dollars at a time (or adding up on our student loan summaries).

New forms of online education like MOOCs lost both forms of primacy at once. By making them free, students had few incentives to not quit any time the course materials got boring or difficult. Without a physical presence, there weren’t the social peer effects of friends encouraging us to attend our classes on time, or shaming us about our poor performance.

These products often tried to emulate the feel of a course by forcing students to take them concurrently. The effect of that model, which Coursera particularly prioritized, appears on the surface to have been unsuccessful, while also reducing the convenience that should be the hallmark of online education.

Open education is absolutely needed – course materials should be distributed as widely as possible for as cheaply as possible. Knowledge deserves to be free. But that openness also makes it hard for these materials to gain primacy in the lives of their students when they are just sitting on the web like every other web page.

From the results so far, it doesn’t seem like we have the answers here yet. Online communication tools have proliferated and significantly improved since the founding of the web, but we still have yet to build the kinds of high-quality and deeply intellectual communities that can handle more than a few dozen members before disintegrating. We need to think about the aspects of primacy we can bring to the web that can rival traditional universities.

Education 2.0?

There are few areas of startups today that continue to be as exciting as EdTech, but we have to be cautious in getting ahead of ourselves. Unlike shopping or socializing online, education is simply not as native an activity for many adults today. We can’t just assume that if we build it, they will come.

Instead, we need to think more deeply about motivation and primacy in order to build a new mix that takes advantage of the internet’s best properties while competing with the quality of the university experience.

Strong examples of this abound already. Duolingo, for instance, uses a mix of spaced repetition methods along with gamification elements to encourage language learners to stay the course. That model emulates certain aspects of physical learning that may be just enough to keep the motivation levels going among students. We will have to see the results in a few years.

Education is crucial for the success of our entire economy. Silicon Valley is right to throw resources at the problem, which remains extensive. However, we need to see humans for what they are, and find the tools and techniques to make sure we help all of us accomplish the dreams we are setting out to do.