Calling

all artists!

UNESCO Bangkok is reaching out to your networks to promote our Happy Schools! Art Contest.

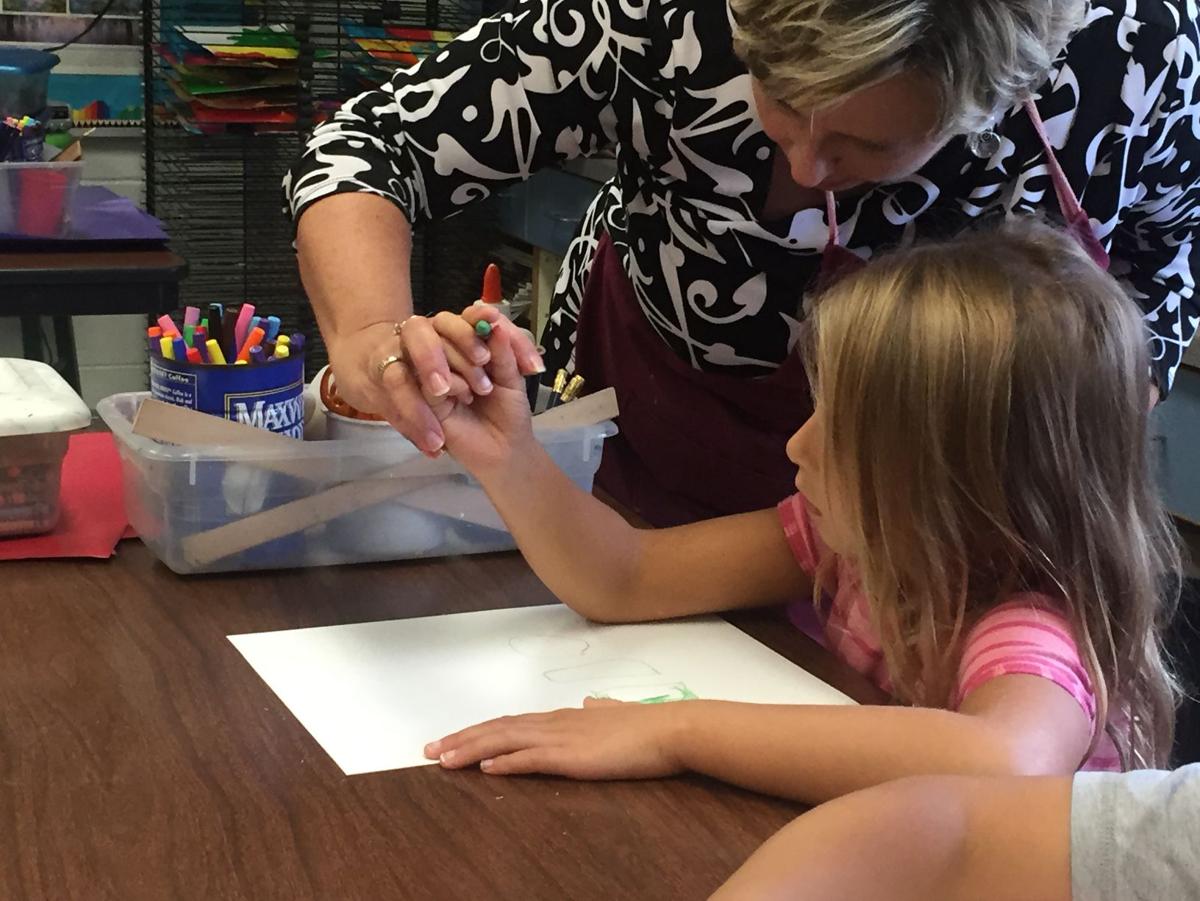

We want artists, illustrators, cartoonists, graphic designers and photographers - students, amateurs and professionals - in the Asia Pacific region to show us:

What does a Happy School look like to you?

Winners will win a trip to Bangkok and invitation to attend a UNESCO launch celebrating the Happy Schools art contest winners - in addition to other cool digital prizes!

As part of UNESCO Bangkok’s Happy Schools Project, this art contest seeks to capture actions, moments and ideas that are promoting happiness in schools.

UNESCO Bangkok is reaching out to your networks to promote our Happy Schools! Art Contest.

We want artists, illustrators, cartoonists, graphic designers and photographers - students, amateurs and professionals - in the Asia Pacific region to show us:

What does a Happy School look like to you?

Winners will win a trip to Bangkok and invitation to attend a UNESCO launch celebrating the Happy Schools art contest winners - in addition to other cool digital prizes!

As part of UNESCO Bangkok’s Happy Schools Project, this art contest seeks to capture actions, moments and ideas that are promoting happiness in schools.

All

residents of the Asia-Pacific region are invited to submit images of any kind

(photos, drawings, cartoons, paintings, graphics, and posters) along with a

caption/description that captures the concept of Happy Schools. We are

accepting entries from all ages in all types of media (entries only accepted in

.jpg and .png format) by 10 January 2016.

We

encourage all interested students and artists to enter. Please pass this along

to any students and artists who might be interested.

Learn more about the Happy Schools! Art Contest here: http://www.unescobkk.org/happyschoolscontest

To enter, fill out the form here.

And upload your entry image(s) here.

For any enquiries about the contest, please contact us using this form.

Learn more about the Happy Schools! Art Contest here: http://www.unescobkk.org/happyschoolscontest

To enter, fill out the form here.

And upload your entry image(s) here.

For any enquiries about the contest, please contact us using this form.