How a New Hampshire school gives its

students more responsibility—and freedom—to shape their academic lives

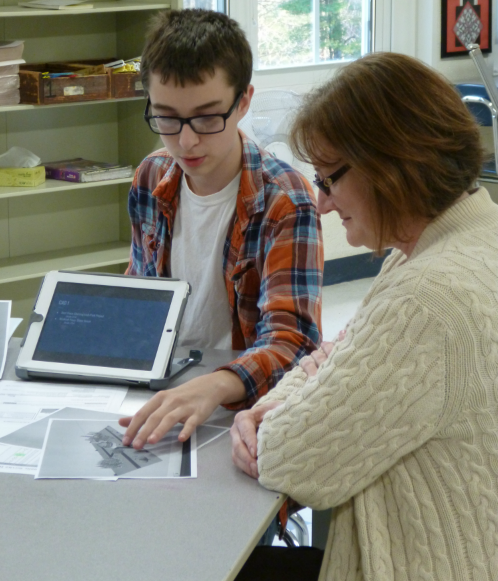

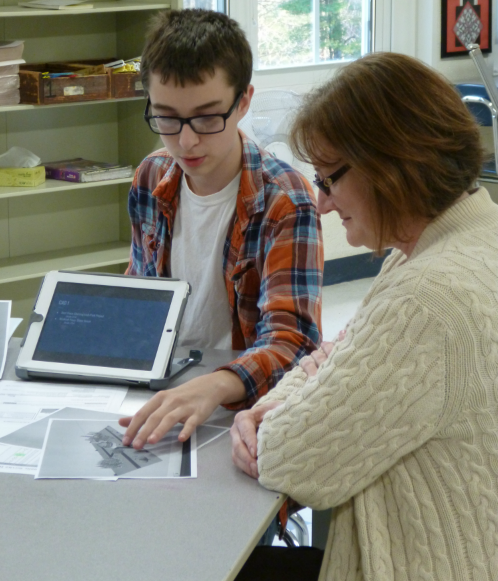

PITTSFIELD, N.H.—Pushing up the

cuffs of his plaid shirt and adjusting his glasses, the ninth-grader Colton

Gaudette looks across the small classroom conference table.

“Welcome to my student-led

conference,” he says.

“Thank you for inviting me,” answers

his mother, Terry Gaudette, sitting next to Colton’s adviser and biology

teacher.

This meeting, which happens twice a

year, has replaced the old format of parent-teacher conferences at Pittsfield

Middle High School, a rural New Hampshire campus that takes a “student-centered

learning” approach to schooling. With this model, students are

given more freedom to connect their individual interests to their academic

learning and future goals. Teachers are considered collaborators and coaches,

and students are expected to shoulder more responsibility for their school

lives—including organizing all the details of these twice-yearly conference

with parents and advisers.

Pittsfield began shifting to this

student-centered approach after being rated one of the state’s

lowest-performing high schools, and qualifying for a federal School Improvement

Grant in 2009. It’s also part of a coalition of 13

New England schools that share another $5 million federal

grant, and was awarded $2 million from the Nellie Mae Education Foundation in

2012, specifically to foster student-centered learning.

“Kids have to be honest with

themselves and I think that’s fantastic,” said Paul Strickhart, who teaches

math at Pittsfield and is Colton’s faculty adviser. “They have to own up to why

they’re not passing a class, or, if they’re doing well, they have to be able to

identify what’s contributing to that and how they can keep going.”

The student-led conferences are also

a way to teach skills you can’t learn from a textbook: organization, long-term

planning, confidence with public speaking, collaboration and self-reflection—even how to shake hands and make introductions in a more

formal setting. That aligns with a larger goal for Pittsfield’s students—to move beyond rote knowledge to develop the kind of

critical-thinking skills needed for “real world” success, said John Freeman,

the district’s superintendent. The unique conference format has helped to

kick-start family engagement, helping the combination middle-high school to

better serve its 260 students and the rest of the former mill town’s 4,500

residents.

Indeed, from New York to Washington State, student-led conferences have

been praised for breathing new life into an otherwise perfunctory process.

According to school officials and families at Pittsfield, before the new format

was adopted a few years ago, turnout for the traditional parent-teacher

conferences was dismal—less than 20 percent participated. Now, more than 90

percent of parents regularly show up.

Students are responsible for writing

a letter inviting their parents or guardians to attend, coordinating with their

faculty adviser to schedule the conference, and preparing a portfolio of their

academic work. The conferences typically last about 30 minutes, including time

for parents to ask questions and for the faculty adviser to give feedback on

the presentation. Students are expected to discuss their academic, social, and

emotional progress and outline their short- and long-term goals.

At the classroom table, Colton lays

out samples of his schoolwork—showing

some of his strongest work and several assignments with which he had less

success. In English class, Colton says he had an easier time crafting his

literary analysis ofLord of the Flies than the subsequent

assignment for The House on Mango Street. He’s working hard to keep

his grade up in geometry, and intends to earn at least a 3.5 (out of possible

4) for both semesters. His geopolitical-studies class is going well, as is

computer-assisted drafting—his blueprints for a set of shelves

turned out better than his first effort designing a stone bench.

Colton also shares the results of

several questionnaires the school uses to help him learn more about his

personality and learning style. The results: “I’m empathetic, artistic, and

kind of shy,” Colton says. His strengths include music, writing, and hands-on

learning. The personality assessments bolster the plans he has for the future:

He wants to study creative writing in college and potentially launch his own

comic-book company. So his biology teacher encourages Colton to look for more

opportunities to connect his artistic interests with his academic learning—he could have gone further with an in-class assignment

asking him to describe the life cycle of a cell, for example.

“I felt down when I got that

[assignment] back and you wrote that we could be more creative,” Colton says.

“I want to try that.”

At the conclusion of the conference,

Colton thanks the adults for participating, and says he is feeling good about

where things stand for him.

“That was very well done, very

thorough,” his math teacher tells him.

His mother is also impressed.

“You’ve been so nervous about this—I think you did an excellent job presenting,” she says. “And

you know how to better prepare yourself for some of this academic work.”

“How many of us appreciated, as a

student, being talked about in the third person as if we were invisible?”

At Pittsfield, students are expected

to begin preparing for the conferences about a month ahead of time, using a

checklist to mark off each of the requirements—including

confirming the meeting times with all of the adults, reviewing their

portfolios, and preparing answers to the self-reflection questions. Lauren

Martin, a Pittsfield senior, said even though it means more work for her, she

prefers the revised format to the traditional conference, which didn’t usually

include the students. Instead, she would have to wait at home for a replay—and then only get her parents’ perspective on the

discussion.

Now, as each semester progresses,

Lauren said she’s keeping an eye out for projects and papers she wants to add

to her portfolio. “It gives me more control of what I share,” Lauren said. “I

know more about my academics than the one teacher who’s my adviser, so it’s up

to me to decide what I’m going to include from each class.”

While not a new idea, the

student-led conference is an approach that’s “gaining speed and traction,” said

Monica Martinez, an education strategist and senior scholar for the William and

Flora Hewlett Foundation. (The Hewlett Foundation is among The

Hechinger Report’s many funders.) The co-author of a book of case

studies examining school approaches to “deeper learning,” Martinez

said the student-led conferences can be a powerful tool for improving students’

engagement with their learning process.

“How many of us appreciated, as a

student, being talked about in the third person as if we were invisible?” Martinez

asked. “When it’s just the teachers and parents participating in the conference

it can end up as ‘we’re going to dictate what you’re good at and what you’re

not good at.’ That’s taking away the power.”

Emily

Richmond / The Hechinger Report

Emily

Richmond / The Hechinger Report

That being said, a student-led

conference by itself won’t mean much, Martinez added. “The school must be

really transferring ownership to the students and making it clear that kids

have plenty of opportunities to reflect on their work.”

Jenny Wellington, an English teacher

at Pittsfield, agrees. The schoolwide shift to student-centered learning is one

key reason that the conferences work, according to Wellington. In class,

students get a say in choosing their academic projects, which not only makes

them more excited about working on their assignments but also about presenting

them at the conferences once they’re completed. She added that parents can also

still getting in touch with teachers at other times to ask questions or to

request meetings.

Pittsfield’s teachers said the

conferences are also an opportunity to observe students’ interactions with

their families, and those moments can be an important window into understanding

their attitudes and classroom behavior. Conferences don’t always go smoothly.

Wellington said she’s observed meetings in which a student’s stated

post-high-school career plans vastly differed from what their families had in

mind. For example, one student was hoping to attend an out-of-state college,

while her parent expected her to stay local or perhaps prepare to work in the

family business.

“That can be heartbreaking,”

Wellington said. “You see the parent maybe trying to push the kid in a

direction that the kid doesn't want to go in, and as their teacher you didn't

know that dynamic was happening at all.”

In such instances, Wellington tries

to encourage the families to use the conference as an opportunity to talk

through their differences. Ideally, the result will be a plan of action that

incorporates the student’s goals while fostering parental support.

To be sure, those kinds of

negotiations work best when teachers know their students well. And Pittsfield’s

small size certainly helps. But Wellington, who taught middle school for six

years in New York City, said she could also see it working in a larger school

setting provided there is a reasonable student-teacher ratio.

“I get to shape my own life starting

here at this school.”

Pittsfield tries to accommodate

parents’ requests to schedule the student-led conferences early in the morning

before class or in the evenings after they finish work, Wellington said. That’s

a better use of her time, she said, than the standard procedure at her old

school in the Bronx, where classes would be canceled for a day and parents had

to show up during that time—or not.

“Usually the parents who did make it

to the conferences weren’t the ones you needed to see. It would be a quick

conversation with me saying, ‘Your kid is doing great, keep it up,’ and that

was it,” Wellington said. “Now the parents are hearing directly from the

students — it’s a completely different kind of conversation, and

it’s so much better.”

While the successes and benefits of

the student-led conferences are widely acknowledged, there is still room for

improvement. Parents of older students have been through the process enough

times that it’s becoming familiar and even rote, said Derek Hamilton,

Pittsfield’s dean of operations. More families seem to be having regular

conversations at home with their kids about their day-to-day academic progress—a very positive development, he added—but that means there isn’t as much new information to share

in the conferences.

To combat that fatigue factor,

Pittsfield is looking for ways to make the conferences more explicitly about

the student’s post-graduation plans and goals and to “raise the stakes” for

their presentations as they advance by grade—maybe by asking juniors and

seniors to present in front of a larger audience, including community members

from outside the school, rather than just sitting at a table with parents and

teachers.

In the meantime, it’s clear that the basic logistics of the

existing conferences are teaching the students important lessons, contends

Hamilton.

“You’d be surprised how many kids struggle to fill out an envelope

to invite their guests to a student-led conference,” Hamilton said. “People

laugh sometimes about the cliché of ‘21st-century skills’ but these are things

every one of these kids is going to need to know how to do in their adult

lives.”

Colby Wolfe, a freshman, has taken advanced math classes since the

seventh grade and said he hopes to follow his mother—an investment

banker—into a career in finance. During his most recent student-led

conference, his adviser told the family that the reports she’s gathered from

his other teachers are highly positive. Because Pittsfield allows students to

take advanced classes once they’ve mastered their required grade-level content,

Colby will have accumulated enough credits by the end of freshman year to be

ranked as a mid-year sophomore.

Part of the reason Colby’s doing so well academically, he said, is

that he gets to choose projects that most interest him and relate to his

post-high-school goals, for example one project where he looked at the

financial aspects of professional sports, incorporating academic work from

several different classes.

“I get to shape my own life starting here at this school,” Colby

said. “I have to say I think that’s pretty cool.”

While it was largely an upbeat conversation punctuated by moments

of genuine humor—his father joked that “this is the most I’ve ever heard

you talk at one time”—Colby didn’t gloss over the facts. He said he’s

finding some aspects of his English class challenging (his grade is the

equivalent of a solid B while he’s getting an A in math), including a recent

assignment that required him to connect a fiction reading to real-life

experiences. He was also disappointed not to have stronger marks in Spanish.

When his adviser mentioned that Colby could speak to the Spanish

teacher about his concerns, the high-school freshman respectfully rejected the

suggestion—at least for now.

“I think I can bring my grade up by doing better on the

assignments,” Colby said, looking around the table at his parents and adviser.

“I want to try that first.”